The Uzbekistan Link: Financial Costs and Strategic Value of China's CKU Railway Project

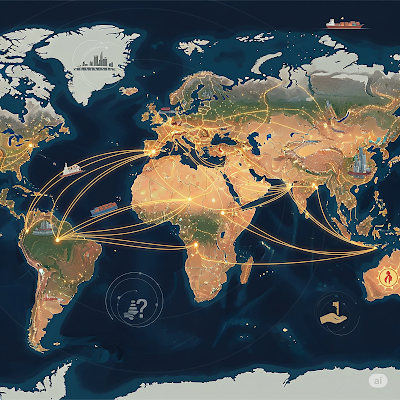

The ambition of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is often described in grand, sweeping terms—a "New Silk Road" spanning continents. Yet, the real story of this massive global undertaking is not found in high-level diplomatic speeches, but in the sweat and steel of individual projects. These are the physical arteries that will either allow the whole system to breathe or constrict its flow.

The ultimate measure of the BRI's success rests not on the number of agreements signed, but on the completion of its most difficult, most strategic bottlenecks. One such choke point, a project delayed for nearly three decades, is the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) Railway. It is a single, critical stretch of track that, once finished, promises to fundamentally reroute trade across Eurasia, bypassing older, politically sensitive corridors. More than just a railway, the CKU line is a testament to the immense financial and engineering will required to carve a new path through some of the world’s most forbidding terrain. Its journey from a proposal on paper in the late 1990s to a construction site today is a fascinating study in geopolitics, debt negotiation, and mountain-conquering engineering.

The Ghost in the Corridor: Three Decades of Delay

The idea for a railway directly linking China, through the spine of the Tian Shan mountains, to Uzbekistan's vast market in the Fergana Valley is not new. A Memorandum of Understanding was first signed in 1997. This seemingly simple project, however, languished for nearly thirty years, a ghost in the grand plans of Central Asian connectivity. The reasons for this lengthy stall were a perfect storm of technical, financial, and geopolitical interests that proved almost impossible to align.

At the heart of the deadlock was a three-way tug-of-war. China and Uzbekistan, both prioritising speed and efficiency for their long-distance trade, favoured a shorter, more direct southern route through Kyrgyzstan. Kyrgyzstan, the transit country hosting the bulk of the construction, pushed for a longer, more circuitous northern route. This longer track would have been far more expensive and slower for the ultimate journey of goods to Europe, but it would have linked Kyrgyzstan’s own underdeveloped northern and southern regions, maximising the domestic economic benefit for Bishkek. For years, neither side would fully concede, transforming the project into a political football.

Adding to the complexity was the resistance from regional heavyweights, primarily Russia and Kazakhstan. For decades, the primary rail route connecting China to Europe—the so-called Northern Corridor—ran straight through Kazakhstan and into Russia. This existing route generated substantial transit fees for both Moscow and Astana. The CKU railway, by offering a shorter, faster, and more southerly alternative, promised to peel away a significant chunk of that lucrative transit traffic. The CKU would, for the first time, allow goods to flow from China directly to Uzbekistan, and from there to Iran, Turkey, and Europe via the emerging Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, widely known as the Middle Corridor. This geopolitical competition meant that the CKU project could not simply be an economic calculation; it was a strategic move that had to wait for the right geopolitical moment to be viable. That moment, driven by new global events that mandated diversification away from the northern route, finally arrived, setting the stage for the crucial financial breakthrough.

The Financial Architecture: Who Pays for the Mountain?

The sheer scale of the CKU project, particularly the construction required in the mountainous Kyrgyz section, meant the final cost was always going to be staggering for the host nations. Initial estimates for the entire line, which stretches approximately 523 kilometres, have varied wildly, often settling between the $4.7 billion $8 billion mark. For Kyrgyzstan, a nation with a GDP that has historically hovered around the $9-10 billion mark, shouldering its share of this cost was an existential financial challenge that threatened to plunge the country into unsustainable debt.

The financing structure, therefore, became the primary obstacle for nearly thirty years. It was only through a major shift in Beijing’s policy that the project found its footing. China ultimately agreed to a structure that de-risked the investment for its smaller, cash-strapped partners. The final agreement, signed in 2024, established a trilateral joint holding company to manage the project. Crucially, the ownership shares were divided: 51% would be allocated to an authorised Chinese company, with the remaining 49% split equally between authorised companies from Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan (24.5% each).

This majority Chinese control is a significant detail. It ensures that China, as the principal investor and ultimate beneficiary of the transit route, has the final say on the project’s management and, most importantly, provides the lion’s share of the financing. Beijing pledged a $2.35 billion low-interest loan to the consortium, a commitment that essentially underwrites the majority of the cost for the critical Kyrgyz section, allowing construction to finally commence. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan still face the significant task of raising their remaining portion, roughly $573 million to $700 million each, but the Chinese pledge was the essential catalyst that overcame the debt-trap fear and unlocked the decades-long stalemate. The CKU railway, therefore, is not just a loan-for-infrastructure deal; it's a strategically crafted corporate structure designed to spread the financial burden while ensuring the project's completion, even if the financial risks for the smaller partners remain considerable.

Conquering the Tian Shan: The Engineering Titanic

The financial difficulty of the CKU pales in comparison to the sheer engineering nightmare that must be overcome to lay the tracks. The 260-312 kilometre stretch through Kyrgyzstan is not merely rugged; it is some of the most geologically challenging terrain on earth. The proposed route must traverse the colossal Tian Shan mountain range, with sections of the track located at altitudes sometimes exceeding 3,000 meters (nearly 10,000 feet).

This terrain necessitates heroic, expensive, and time-consuming construction. The Kyrgyz section alone is slated to require the boring of over 50 tunnels and the erection of close to 90 major bridges. Tunnels are not simple drill-and-blast jobs here; they are deep, long excavations—the proposed total length of tunnels is over 120 kilometres—that face a daunting combination of hazards. Engineers must contend with high ground stress deep within the mountains, a constant threat of high seismic activity (earthquakes are common in the region), and the logistical nightmare of construction at extreme high-altitude cold. Projects like the Fergana Mountain and Koshtube tunnels are not just infrastructure; they are monuments to industrial perseverance against nature, utilising specialised equipment and techniques for high-altitude, cold-weather geology.

Beyond the mountains, a second, more subtle engineering challenge has complicated the project for years: the gauge disparity. China uses the standard gauge (1,435 mm), which is common across much of the world. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, however, inherited the wider Russian-era broad gauge (1,520 mm), a relic of the Soviet rail network. This difference means that train wheels cannot run seamlessly from one country to the next.

For years, the three countries debated whether to build the Kyrgyz section to the Chinese gauge, the Soviet gauge, or even a dual-gauge system. A consensus has emerged for building the line to the Chinese standard (1,435 mm) through Kyrgyzstan to the final stop in Uzbekistan's Andijan. This choice means that at the border with Uzbekistan, all cargo will have to be transshipped—moved from the narrower Chinese wagons onto the broader Uzbek wagons—or complex, time-consuming wheel-changing operations will be necessary. While this sounds like a logistical headache, the agreement to standardise the new line on the Chinese gauge up to a fixed point signals a clear commitment to facilitating the fastest possible trade flow from China, prioritising the corridor’s long-term commercial efficiency over simple technical uniformity with the existing local network. It is a necessary friction point built into the design, but one that ensures the strategic speed of the overall route.

The Uzbekistan Link: Material Impact on Local Commerce

The CKU project is the physical embodiment of Uzbekistan’s national strategy to become the undisputed transit hub of Central Asia. Geographically, Uzbekistan is one of only two double-landlocked countries in the world (surrounded entirely by other landlocked nations). Breaking out of this geographic constraint is essential for its rapidly growing economy. The CKU line offers the shortest, most direct artery from the densely populated Fergana Valley—Uzbekistan’s industrial heartland—directly to China.

For Uzbek and Kyrgyz commerce, the material impact of the CKU is measured in time and money. The project is estimated to reduce the journey for freight from China to markets in the Middle East and Europe by up to 900 kilometres and, critically, shorten the transit time by a full week, from approximately two weeks to just seven days. For businesses, a week saved in a global supply chain is a massive competitive advantage. It lowers the cost of goods, reduces inventory holding expenses, and makes Uzbek products, from textiles to agricultural exports, far more viable in international markets. The line is projected to handle 15 million tons of cargo annually, a major leap in capacity for the region.

Furthermore, the local economic injection is significant. The construction phase alone will generate thousands of jobs in both Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, and the long-term operation of the line promises to be a stable source of revenue. Both Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan stand to gain an estimated $150 to $200 million in annual transit fees from the foreign cargo passing through their territory. For a country like Kyrgyzstan, this transit revenue represents a vital, diversified income stream that can help manage its considerable external debt obligations. The CKU also connects directly with existing domestic infrastructure in Uzbekistan, notably the Pap-Angren railway (a domestic link financed by China eight years prior), further integrating the Fergana Valley into the Eurasian trade network and reinforcing Uzbekistan’s position as a regional nexus.

The Strategic Value: Re-drawing the Eurasian Map

The strategic value of the CKU railway transcends local economics; it is a vital pillar of the broader Eurasian geopolitical landscape. By creating a functional, direct route from China through Uzbekistan, the CKU achieves two key strategic goals for the BRI.

First, it is the crucial "missing link" for the Middle Corridor. The Middle Corridor is the alternative trade path that crosses the Caspian Sea, connecting Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan) to the South Caucasus (Azerbaijan, Georgia) and then to Turkey and Europe. Without the CKU, this corridor relies on much longer routes through Kazakhstan or the existing, fragmented road-rail links through Kyrgyzstan that require multiple complex transfers. The CKU transforms the entire equation, providing a high-speed, high-capacity land bridge to the Caspian Sea, making the Middle Corridor genuinely competitive against the traditional Northern Corridor through Russia.

Second, the CKU is a masterful piece of geopolitical diversification for Beijing. The outbreak of the conflict in Ukraine and the resulting Western sanctions on Russia severely disrupted the Northern Corridor, forcing global commerce to seek alternatives. The CKU's final push for construction came precisely at this geopolitical juncture, proving its value as a resilient alternative route. By fostering direct trade links that bypass its traditional Russian ally, China not only increases its own strategic leverage in Central Asia but also provides its Central Asian partners, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, with a degree of economic independence and security through route diversification. The railway is, therefore, a tangible, physical expression of China's growing, indispensable influence in a region that was once viewed exclusively as Russia's "near abroad."

Ultimately, the CKU is more than just a railroad; it is a strategic decision that has been three decades in the making. It is a calculated leap of faith by China, a massive debt negotiation for Kyrgyzstan, and an economic lifeline for Uzbekistan. The project will redefine transport costs, reallocate trade revenue, and rebalance geopolitical influence across the entire Eurasian continent. The challenges of its financing were immense, and the engineering required to bore through the high, seismic spine of Central Asia is historic. Yet, the agreement to finally lay the steel, driven by the strategic imperative of the Belt and Road Initiative, signals the end of the CKU's long stall and the true beginning of a new, shorter Silk Road. The "Uzbekistan Link" is set to be one of the most transformative transport projects of the 21st century.